Following a successful radical pub crawl across Peckham, New Cross and Deptford last year, myself and about two-dozen comrades came together to celebrate the working-class history through the boozers of different area of south-east London: Forest Hill, Sydenham and Catford.

Why Forest Hill, Sydenham and Catford?

In part, it is because of live in this area. In the spirit of movements such as History Workshop and “Dig Where You Stand”, I’ve been conducting a larger independent research project into the working-class history of the area, to further understand the conditions and struggles that have made the area I live in what it is today, and may inform our future struggles.

It is, however, also in part a reclamation of the area as a site of class struggle. Often, perhaps wrongly, seen as a residential suburb, it is easy to overlook the area as one of class struggle. But workers’ exist everywhere, and every area has been formed and reformed throughout history through their struggles. As the details of this walk will tell, the working-class of this part of south-east London made their mark not jus on their own area, but also on the wider city, and indeed country.

It is from this context that we start our pub crawl. Onwards comrades!

#1: The Greyhound, Sydenham

We start at The Greyhound next to Sydenham station. Now a somewhat bougie gastropub, there has been a pub in some form on its site for many years since 1720. In 1754, George Thornton, the landlord of the pub then known as The Greyhound Inn, helped set a historical precedent in the area for wanky small businessmen. He and his pub were the target of agitators amongst the local poor fighting against the enclosure of Sydenham Common from Cooper’s Wood, where The Greyhound Inn was based. Along with others who had encroached onto this common land to privatise it, his fences were consistently thrown down by the angry local poor who insisted on maintaining their right of access to the wood.1

That wouldn’t be the only struggle over the pub however. Almost 300 years later, in 2012, The Greyhound was illegally demolished by the development company Pure Lake, leaving only the front wall intact. The pub is in a conservation area, meaning its demolition could not happen without council consent, which hadn’t been granted. Although Pure Lake had been fined £5,000, as well as being ordered to pay £13,000 court costs, local community members did not believe this outcome went far enough.

Through the “Sydenham Society”, they organised a petition with well over a thousand signatures, demanding the pub be rebuilt for the community by Pure Lake. On October 1st 2014, they picketed the council headquarters in Catford, where they confronted the Mayor of Lewisham, Steve Bullock, chanting “Enough is enough, we want our pub back!”. Eventually their actions forced the council to issue an ultimatum later that month to Pure Lake, who had to start rebuilding a new pub on the site in 2014, completing the works in 2018.

#2: Fox and Hounds, Sydenham

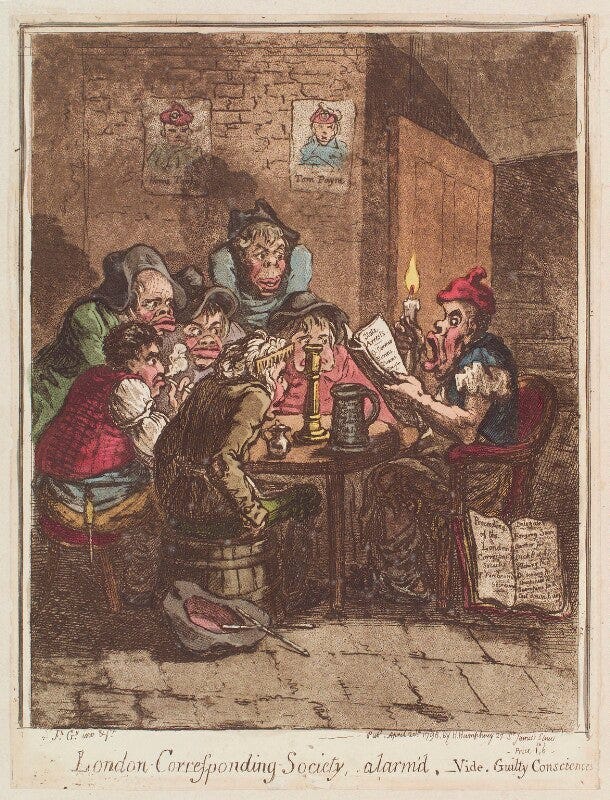

Again, our next pub has also been around for a long time. The Fox and Hounds in Sydenham was home to a meeting on 16 July 1795 by local radicals. These locals met to express interest in founding a local division of the London Corresponding Society (LCS).2

The LCS was a federation of local “reading and debating clubs” that was founded in the 1790s following the French Revolution, and agitated for radical and democratic reforms in Britain. Marxist historian E.P. Thompson describes the LCS as key to the emergence of working-class consciousness in Britain, as its open membership and low subscription rates invoked “a new notion of democracy, which cast aside ancient inhibitions and trusted to self-activating and self-organising processes among the common people.” Many members of the LCS, whose membership peaked at around 5,000, were harassed by the police, and arrested under Pitt the Younger’s suspension of Habeas Corpus.

It was particularly significant for such an LCS branch to form in Sydenham, which at the time was part of Kent, and had yet to see the significant growth in urbanisation and industrialisation that would follow there in the early 19th Century. The new group in Sydenham was to be the 52nd division of the Society. Several of the leaders of the Society were to attend the meetings in Sydenham, including Francis Place, a radical social reformer who many years later would later be successful in agitating for the repeal of the 1799 Combination Act which had banned the formation of trade unions.

Some later meetings of the LCS Division 52 seemingly happened at the Golden Lion pub, just down the road. Post from the general committee to the division was sent to the Golden Lion’s address, where it was intercepted by a treacherous pub landlord and forwarded to the Greenwich Justices of the Peace!3

#3: The Dartmouth Arms, Forest Hill

Moving into Forest Hill, our next pub is The Dartmouth Arms. Now owned by Meatliquor and adorned with neon-lights that sting your eyes from all angles, a pub has sat on this site since 1815, being one of the first opened since the enclosure of the common. However, a particularly momentous date in its history was Sunday 13th September 1964. On this day, three black activists Geoffrey Browne, Roy McFarlane and George Brown, as well as Hong Kong born Sydney Hollands,began a sit-in inside the pub, over its refusal to serve non-white customers in the saloon area of the bar. Geoffrey Browne, who worked in Lewisham, had been refused service earlier that month due to the pub’s colour bar, and Roy McFarlane was secretary of the local International Brockley Fellowship Association.4 Inspired by similar sit-ins organised by the Civil Rights Movement in the US, their action launched a struggle by local community members against the pub’s racist colour bar.

Anti-racist protestors would stage another sit-in outside the bar in December that year, and in January 1965 over 50 people picketed the pub demanding an end to its racist policy. The pub’s landlord, Harold Hawes, relied on the support of local fascists in resisting this community action - even refusing to serve the Mayor of Lewisham when he tried to buy a drink for Melbourne Goode, a local black activist. Later on in 1965, the British government passed legislation making it illegal to refuse to serve customers based upon their race, although Harold Hawes would continue to implement his racist colour bar for long after this law was put into action.

The initial sit-in by Geoffrey Browne, Roy McFarlane, George Brown and Sydney Hollands that inspired this campaign is an important part of local anti-racist history. However, as well as their tactics, their class position also mirrored that of the US civil rights movements. All were either managers or company directors - a far cry from the working-class reality of most in South London’s racialised communities. At various points in history, black activists have often criticised the motivations of upper and middle-class leaders in the civil rights movement, as neglecting the concerns of working-class black communities in favour of those concerns that would see greater integration for the black middle-class into its white counterpart.5 When conducting further research into the movement against the Dartmouth Arms’ colour bar, it would be interesting to investigate more, to see if these class tensions played out within it too.

#4: All Inn One, Forest Hill

Crossing below the station underpass, we move onto All Inn One. On Tuesday 12th November 1889, this pub, at the time called the Forrester’s Tavern, was the meeting place of a group of master bakers6, representing the bakeries of Forest Hill, Sydenham and Catford. The master bakers were meeting over the threat of strike action by local bakery workers, who had recently formed a “Strike Union”.

This was part of a larger movement of bakery workers in London, who. After mass meetings in Hyde Park, a strike committee had been formed by the Amalgamated Union of Operative Bakers (now known as the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers' Union), and workers across the capital threatened to walk out on November 16th of all bakeries that had yet refused to meet their demands, namely a reduction of working-hours to 60 per week.7

These workers were inspired by the wave of “New Unionism” sweeping the country. This “New Unionism” had been bolstered by the matchstick girls strike in 1888 and the London dockers’ strike in 1889. It placed emphasis on organising both unskilled and skilled workers, as well as prioritised militancy and a willingness to take industrial action.

The master bakers voted to agree to the workers demands around reducing working whilst keeping existing wages, but on the condition all overtime was paid for on the normal hourly wage. Two days later, on Thursday 14th November, the bakery workers voted to accept this offer from the master bakers.8

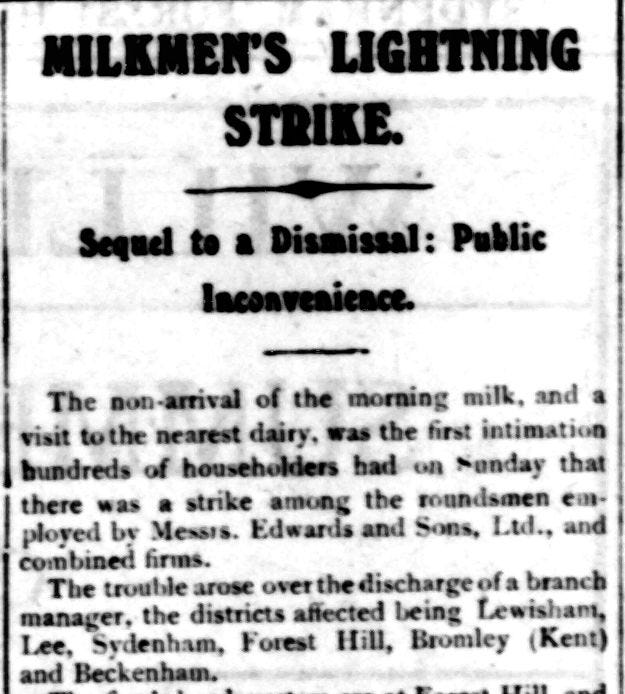

Perry Vale was also the site of several wildcat strikes by milk carriers in the 1920s, he largest of which was in April 1925. The Forest Hill milk carriers met in an unnamed local pub, and voted to strike from the next day. The following morning, 300 milk carriers employed by the company downed cans, demanding a minimum wage of £4 a week, a six day week, and 14 days paid holiday. This strike soon spread out beyond Forest Hill, covering most of London, before workers were coerced back to work by both their union and the dairy companies a week later.9

BONUS STOP: Forest Hill Sainsburys

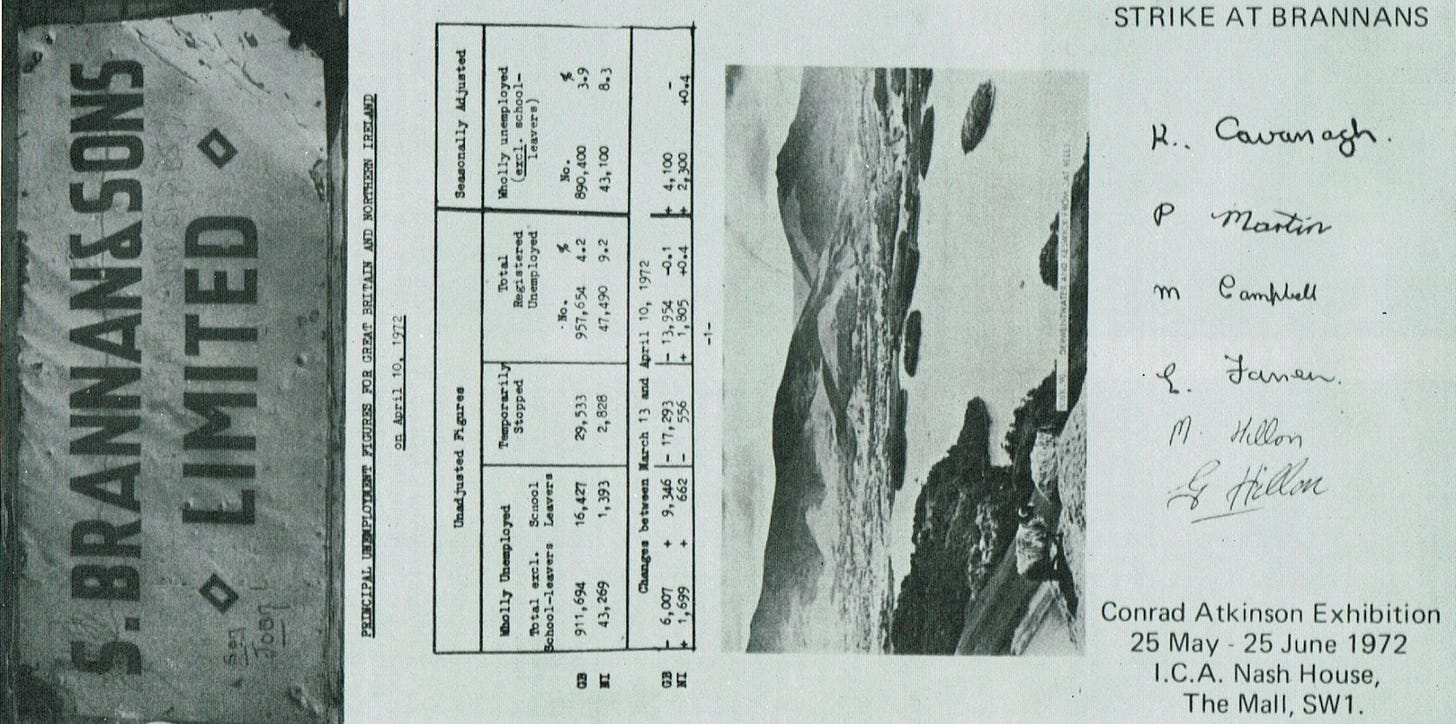

In May 1972, artist Conrad Atkinson’s exhibition ‘Strike at Brannans’ opened at the ICA. The exhibition had been produced in collaboration with a group of workers involved in the ongoing strike at the Brannon thermometer factory in Atkinson’s hometown of Cleator Moor (in Cumbria). The primarily women workforce had initially demanded equal pay, as they were currently paid only 70 percent that of the men in the factory. However, when this demand was met, the strike’s demands focused on their working conditions. Work in the factory involved dangerous levels of exposure to mercury, to the indifference of the company managers, and the strikers pushed for great workers’ control of the production process, to enforce proper health and safety for those in the factory.

A group of women workers at the Forest Hill Brannans factory, which had been un-unionised, organised a trip to the exhibition, which would also be addressed by two visiting strikers from the Brannans factory in Cumbria.

Throughout the strike, the owner of Brannans had threatened to close his factory in Cumbria, and move his entire operation to the Forest Hill factory. However, Conrad Atkinson visited the Forest Hill factory, taking pictures he then shared with the visiting Cumbria strikers. Recognising that the facilities in London were currently totally unsuitable for such a move in production, the two visiting strikers then met with the Forest Hill workers and encouraged them to unionise their own factory.10

This trip to the exhibition and meeting with the Cumbria strikers then inspired the Forest Hill workers to organise a union campaign in their factory. They would quickly become 100% unionised with the AUEW.11 Sadly, the strike in Cumbria ended not long after, so the Forest Hill workers did not join. The Forest Hill factory would be closed the next year in 1973, with workers unfortunately failing to save their jobs despite their remarkable unionisation the previous year. The factory’s former site is now part of the Sainsburys on London Road in Forest Hill - where if you wish you can grab a tinnie for the long walk to our next pub.

#5: The Duke of Catford, Catford

The pub currently known as The Duke of Catford has gone through many awful iterations. Until recently, it was known as “Ninth Life”, pairing overpriced pints with the most garish decor you could imagine. Reopening under the Duke of Catford, it has somehow become worse. The beer garden is locked up, they seemingly have no beers stocked on tap, and an imaginably dead atmosphere.12

However, back in the 19th Century it was a boozer with a different type of clientele. Back when it was known as “The Black Horse and Harrow”, it was a regular drinking spot for critic of political economy and communist don Karl Marx. We drink on the shoulders of giants comrades!

#6: Blythe Hill Tavern, Catford

Admittedly we have cheated a bit with our final pub - we are finishing here simply because it is a fantastic boozer to end the night in. However, a few doors down on the corner of Stanstead Road and Elsinore Road is the previous site St James Hall, an important venue for Lewisham’s working-class history. Amongst the political rallies and meetings that have happened in his hall was a well-attended protest meeting held 23rd May 1901 by Camberwell Municipal Labour Union.

This meeting was called to campaign against the “starvation wages” being paid to Lewisham Borough Council employees. It was also supported by members of Tram and Bus Workers Union, whose members attended in solidarity. The Camberwell Municipal Labour Union had formed just over a year earlier, representing workers including sweepers, pickers, dustmen, dustboys, flagmen, carmen, sewer-flushers and other workers in Camberwell and neighbouring boroughs. One of its key aims was to win a 30s minimum wage, and had already helped win a substantial pay rise for workers in its home borough of Camberwell.13

Lewisham Borough Council itself was also only formed the year before, and paid its workers far less than other councils. For instance, dustmen earnt 7s 3d less per week than Southwark, the next lowest paying council. The category of "dustboys" were paid even less, earning 10s a week - with many of these workers not even being “boys”, but adult married men! Workers in Lewisham also worked 56.5 hours a week, which was far higher than in other south London boroughs. The union also campaigned against attempts by Lewisham Council to get workers to work a 7 day week, with no overtime on Sundays.14

The mayor of Lewisham responded negatively to the union's demands, claiming the concerns of the union’s members in their borough’s workers’ affairs was an example of unnecessary “outside influence”. The union and it allies defended itself from these attacks, with even the Lewisham Borough News, arguing that:

"the wages and hours question, or to put it shortly, the cause of Labour, is too important an element in our social system to be cribbed, cabined and confined within the limits of any single borough”15

A union branch for Lewisham borough workers was formed shortly after (perhaps the Camberwell unionists had a drink at the Blythe Hill Tavern to celebrate!), so this agitation was, in many respects, successful. After many amalgamations and renamings, that union branch lives on today, in the form of Lewisham Unison. Lewisham Unison was the site of intense struggle last year after the council tried to sack it’s two branch secretaries, seemingly in an attempt to bust the union before implementing millions of pounds worth of cuts.

So next time you’re boozing in the Blythe Hill Tavern for the rest of the night, raise a glass to all those workers who’ve fought for themselves in this area before us, and all those who will inevitably fight in the future to come.

Betty O’Connor (2009) Rights of the Common: The Fight Against the Theft of Sydenham Common and One Tree Hill.

ed. Mary Thale (1983) Selections from the Papers of the London Corresponding Society 1792-1799. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pg. 304.

David Jesudason (4 October 2024) 'Dartmouth Arms, Forest Hill - Fighting for different versions of the future', Episodes of My Pub Life.

August Meier and Elliott Rudwick's history of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in the US offers many critiques in this regard, such as around CORE's earlier housing campaigns:

"Prior to the latter-half 1963, CORE housing projects were practically all devoted to securing homes and apartments for middle-class blacks in white neighbourhoods. CORE people in this period were thinking more in terms of breaking up the ghetto than in making them more livable." - pg. 184

For more, see August Meier and Elliott Rudwick (1973) CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights Movement, 1942-1968. New York: Oxford University Press.

Side note: when saying “master bakers” out loud multiple times in a talk, some of your friends are probably going to giggle at you.

(8 November 1889) ‘Impending Strike of Bakers’, London Evening Standard.

(16 November 1889) ‘Threatened Strike Among Local Bakers Averted’, Sydenham, Forest Hill and Penge Gazette.

I will describe this strike and others by Forest Hill milk carriers in detail in a later post.

Atkinson’s full account of his exhibition and the struggle of the Brannan's workers can be found in: Conrad Atkinson (1981) Conrad Atkinson: Picturing the System. London: Pluto Press.

Geoffrey Sheridan (11 August 1972) 'When the solidarity fails', The Guardian.

The Duke of Catford seemingly shut down the week after we visited, with little-to-no information as to why. Whether another iteration of a pub will be re-opened on this site is yet to be seen.

(13 April 1901) ‘Camberwell Labour Union’, South London Mail.

(30 May 1901) ‘Lewisham Borough Council's Starvation Wages’, Lewisham Borough News.

(13 June 1901) ‘“Outside Interference”’, Lewisham Borough News.